Introduction

PART ONE: Systems Thinking in Revenue Operations

The CFO in the Middle of Everything

Across three decades, I have occupied a seat that looks deceptively narrow on an org chart but touches every nerve center of a modern enterprise. Officially, it reads “Chief Financial Officer,” but in practice, it has felt more like the Chief Synthesizing Officer, one who must integrate the fragmented truths from sales, marketing, operations, and engineering, and stitch them into a coherent narrative of performance, risk, and growth. This is especially true in the area that most confounds growing companies: revops. Over the years, my work driving CFO strategies and CFO business strategies, offering CFO advisory services, and serving as a fractional CFO or providing fractional CFO services, has reinforced that revenue operations is where clarity meets execution.

I do not say this lightly, but in every organization I have helped scale or realign, revenue operations has offered both the richest opportunity and the most significant dysfunction. The dysfunction never shouts. It reveals itself in slippage, in missed forecasts, in deals stuck in legal review, in discounting that slowly becomes a habit. It whispers through misaligned incentives, tribal process hacks, and inconsistent application of policies. But it always shows up in the numbers eventually. And the numbers, if we have the humility to listen, whisper before they scream.

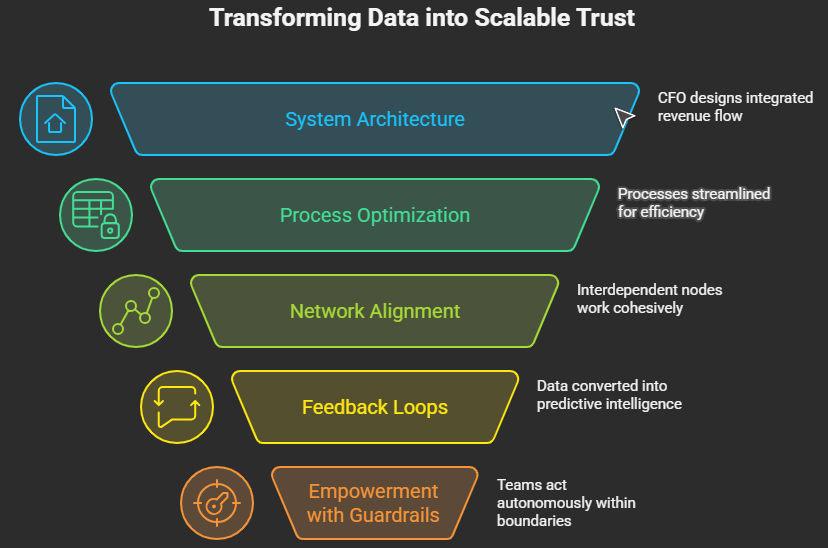

Over the years, I have come to see this arena not as a battleground between control and agility, but as an orchestration challenge. The real task is not optimization, but coordination. Not speed, but flow. And like all orchestration, it only works when you understand the score beneath the noise.

Complex Systems and Revenue Design

In my work, deeply influenced by systems theory, search theory, and information economics, I have always viewed businesses not as mechanical engines but as complex adaptive systems. These systems do not behave linearly. Input does not reliably produce outputs. Feedback is often delayed, distorted, or drowned out. Decisions under uncertainty require more than dashboards. They need designed listening, strategic iteration, and a culture that distinguishes signal from noise.

This lens radically reframes how I think about revenue operations. Rather than treat sales, marketing, finance, and legal as sequential handoffs in a pipeline, I treat them as nodes in a dynamic, evolving network. Each node produces signals. Each node consumes signals. Misalignment is not just a coordination problem; it is a breakdown in system intelligence.

Take pricing approval. In most organizations, this becomes a frustrating bottleneck. Sales wants to move quickly. Finance intends to preserve margins. Legal wants risk protections. Each team acts rationally in its silo. But the overall system behaves irrationally because no one designs the incentives, data visibility, or authority boundaries with the system’s adaptive nature in mind.

I have redesigned approval processes that once took six days and made them operate in under six hours, not by cutting corners, but by redesigning the flow. We codified pricing parameters by region and product line using real deal velocity data. We embedded automated guardrails in CPQ systems. We created escalation paths that respected time zones, decision rights, and thresholds. Most importantly, we institutionalized “flex with accountability.” That meant sales reps could flex within board-approved discount limits, but any outliers triggered not just approvals but learning loops.

This matters not just for speed, but for intelligence. A deal with an unusual discount is not just a risk. It is a data point. Is the product mismatched? Is the competitor bundling differently? Are we missing regional sensitivities? Every exception tells a story if we build the system to hear it.

The Illusion of Process and the Reality of Friction

In one of my earlier experiences at a hypergrowth software firm, I walked into a revenue process that looked pristine on paper. The QTC process included 37 steps, 10 validations, and multiple audit trails. But deals still leaked margin. Customers grew frustrated with delays. And sales reps began writing workaround playbooks to “get things done.”

This is what I call the illusion of process. It feels safe. It looks comprehensive. But it produces friction at scale. Every team defends its step. Yet the whole breaks down because no one owns the flow. That is the crucial insight. In systems thinking, local optimization often degrades global performance.

We dismantled the bloated structure not by eliminating rigor, but by shifting focus. Instead of asking, “What step does this serve?” we asked, “What signal does this generate?” Every step in a process should either reduce risk, accelerate flow, or enhance learning. If it does none of the three, it should be redesigned or removed.

The most powerful change was not technical. It was narrative. We reframed operations as a customer experience function that served not only the buyer but the seller. Suddenly, legal saw their SLA not as a gate but as a promise. Finance viewed approvals as time-sensitive value protectors, not veto power. And sales stopped gaming the system because the system stopped gaming them.

Deal Desk: Where Control Meets Trust

No function in revenue operations embodies this balance more than the deal desk. In weak organizations, the deal desk becomes a bottleneck where innovation dies and trust erodes. In strong organizations, it becomes a strategic command center, a hub of intelligence, guidance, and trust.

I have built and led deal desks that do not just vet pricing but also analyze pattern shifts in buyer behavior. We track the number of red lines, the time to signature, the discount bands by industry, and objection types by persona. We marry these with win/loss data to forecast which deal structures drive conversion, not just closure.

But here is the deeper point: a good deal of desk education serves to educate the system. When sales know the top three reasons deals stall in procurement, they adjust proposals. When a product faces recurring feature pushback due to legal redlines, they reconsidered for bundling. When finance sees how discounting behaves across regions, they revisit tiering.

In short, the deal desk is not a gatekeeper; it is a signal amplifier. It operates at the intersection of structure and flexibility. It maintains the brand, protects value, and accelerates flow. But only when designed with trust.

The Adaptive Nature of QTC (Quote to Cash)

Quote-to-Cash is often described as a process, but I have come to view it as a nervous system. It touches pricing, contracts, billing, compliance, revenue recognition, and customer onboarding. Every misfire in QTC sends shockwaves downstream. Every improvement creates compounding benefits.

I once worked on an end-to-end rearchitecture of QTC that required balancing dozens of systems: CRM, CPQ, ERP, legal repositories, and support platforms. But the most significant insight was not technical; it was systemic. Most delays did not arise from system limitations. They arose from ambiguity of ownership.

We solved this by creating what I call Revenue Flow Maps ( I picked this up in my Design Thinking class at Lead Innovation at Stanford University), which are diagrams that trace each decision point, handoff, and potential failure mode. We color-coded delays by root cause: people, process, platform, or policy. Then we assigned response teams not by function, but by flow path. Suddenly, engineers were working alongside revenue ops, legal, with support, and finance, with onboarding.

And what happened? Time to invoice dropped 28%. Time to cash dropped 22%. And customer satisfaction rose because QTC stopped feeling like bureaucracy and started functioning like a designed experience.

PART TWO: Intelligence Loops, NPS, and Strategic Execution

Feedback Loops: NPS as Signal, Not Score

If there is one metric that evokes both obsession and skepticism in boardrooms, it is the Net Promoter Score. For years, I regarded it with cautious curiosity, drawn to its simplicity, wary of its limitations. Over time, however, I have come to recognize its true utility. NPS is not a judgment. It is a pulse. And like all vital signs, it must be interpreted in context and observed over time.

In its purest form, NPS asks a single question: “How likely are you to recommend this product or service to a friend or colleague?” The answer, on a scale from 0 to 10, classifies customers into promoters, passives, and detractors. The resulting score: promoters minus detractors serves as a crude but valid proxy for loyalty.

But the score, standing alone, tells us very little. What matters is the signal buried within the score. What has changed since last quarter? Which segment is diverging? Where is the anomaly, the hidden pocket of satisfaction, or the latent discontent?

We began correlating NPS deltas with churn risk, feature usage, support responsiveness, and implementation timelines. We segmented by customer cohort and mapped NPS trends against account growth and contraction. What emerged was a living model of customer health, a system of feedback loops.

Churn, LTV, and the Cost of Not Listening

Churn is the tax we pay for failing to listen. It is the penalty for ignoring signals, misreading intent, or allowing small frictions to calcify into grievances. In financial terms, it is the silent destroyer of Lifetime Value (LTV). And in operational terms, it is almost always a systems failure and not necessarily a customer failure.

We modeled churn across customer segments and mapped it against NPS responses. The correlation was sobering. Detractors churned at more than triple the rate of promoters. But more revealing were the passives. Their churn rate hovered dangerously close to that of detractors, especially in our SMB segment. It turns out, indifference is nearly as fatal as discontent.

Promoters had LTVs more than 4 times those of detractors. These findings confirmed a belief I had long held: loyalty is not a qualitative attribute. It is a quantitative asset that accrues interest just like capital.

One feature —a data visualization tool in DOMO —had an outsized impact on NPS improvement. Those who used it regularly were far more likely to become promoters. That signal became a strategic lever. We redesigned onboarding to emphasize early exposure to that feature. Within one quarter, NPS in that cohort improved, and so did expansion bookings.

Empowerment and Guardrails: Building an Approval System That Breathes

Pricing and discount approvals often create the most significant friction. Sales wants speed and flexibility. Finance wants discipline. Legal wants protection. Marketing wants brand integrity. These competing needs usually produce rigid approval matrices that resemble a fortress: defensible, but immobile.

I build systems that empower teams to act quickly within board-approved bounds. Beyond those bounds, escalate with precision and purpose.

We classify deals into archetypes like standard, strategic, custom, and exception. Each archetype carries its own rules. And each exception becomes a learning opportunity. Why did we approve it? Did it perform? What surfaced during legal review that we missed in the pre-deal stage?

Over time, we revise thresholds through pattern recognition. Our system breathes. It adapts.

For the CRO, this brings agility. For the CFO, confidence. For sales, trust. And for the company, execution consistency without rigidity.

From Analytics to Action: Making Systems Learn

Data without action is trivia. Action without feedback is noise. True intelligence in revenue operations emerges when analytics and operations form a loop.

We tag every contract with metadata. We link CRM activity with onboarding velocity. We score deals not just by size, but by friction profile. Then we close the loop.

Deals with three or more legal revisions had a 30% lower renewal rate. We trained sales on simplification, built fallback clauses, and reduced redlines. Renewal rates improved. Sales efficiency rose.

This is adaptive systems engineering. And it lies at the heart of every high-functioning revenue machine.

Conclusion: The CFO as Systems Architect

Value creation is a systems outcome. It emerges from the alignment of feedback, incentives, design, and decisions. Revenue operations is not a back-office function. It is the central nervous system of the modern enterprise.

As CFO, I do not merely track numbers. I track signals. I do not merely approve of spending. I design flow. I do not simply enforce policy. I am an architect of intelligence.

In a world where complexity compounds, the edge lies not in data volume, but in system adaptiveness. The organizations that learn faster than they forget will not only survive, but they will also define the standard.