Introduction

Startups are built on vision, hustle, and the courage to step into chaos. Founders are trained to pitch their product, scale their customer base, and inspire investors with their narrative. But amid that momentum, the very first mistake most startup founders make is neglecting the quiet fundamentals, especially tax planning. Among the most popular mistakes startups make today, few are as costly as overlooking tax issues for startups, which can compound silently until they threaten liquidity or valuation. In my three decades as a CFO across industries from SaaS and cybersecurity to logistics and gaming, I have seen these startup mistakes play out repeatedly. Ultimately, mistakes startups make around compliance and taxation are not side issues; they are valuation killers.

I learned early in my career that chaos and order coexist. In systems theory, order often emerges from patterns hidden inside apparent disorder. Finance and tax follow this principle. On the surface, a startup’s first year may look like a whirlwind of receipts, payroll, and investor decks. Underneath, every transaction has a story, and every story has a tax footprint. Some footprints, if ignored, compound into financial entropy that erodes trust. Others, if tracked with foresight, become invisible stabilizers that preserve credibility and enhance investor confidence.

In Silicon Valley, I have worked with companies that scaled from $10 million to $100 million, and I have seen how the smallest early tax choices ripple into massive long-term effects. I maintain a personal network of Bay Area tax advisors who bring deep expertise in international tax compliance, R&D credit documentation, equity compensation taxation, and M&A structuring. Founders who bring these advisors into their strategy early consistently outperform those who delay. The tax system does not forgive ignorance, but it rewards preparation.

One Series B logistics startup I advised discovered during diligence that its remote workforce tax obligations created filing exposure in six states. Because they had never registered, the valuation haircut during funding negotiations was steep. Another SaaS startup I partnered with missed timely 83(b) elections for multiple employees. What seemed like an administrative oversight turned into millions in unexpected equity taxation at exit. These examples prove a critical point: taxes do not simply exist at year-end. They are evident every day in how a company is structured, how expenses are classified, how equity is documented, and how compliance is managed across different geographies.

This blog is not about scaring founders into compliance. It is about showing that tax can be leveraged as a strategic growth tool. Just as systems thinkers see patterns inside complexity, founders can find hidden advantages inside tax rules. A proactive stance allows startups to harness QSBS eligibility, R&D credits, clean cap table management, and multi-jurisdictional compliance as value drivers rather than distractions. The goal is simple: reduce entropy, build trust, and preserve capital.

In the following sections, I will outline the five foundational areas of startup tax planning:

Entity structure, expense classification, equity documentation, nexus tracking, and advisor engagement. Each section dives deep into why it matters, how I have seen it mishandled, and how to build lasting resilience.

At the end, I will also share the Top 20 Tax Mistakes for Startups from Series A through D, including those with international subsidiaries, as a checklist founders can reference with their boards and advisors.

The Entity Decision Isn’t Just Legal—it is Strategic.

The incorporation decision, for most first-time founders, defaults to Delaware C-Corporation status. This is the standard recommendation from accelerators, investors, and legal counsel, and it usually makes sense. C-Corps simplify fundraising, allow for multiple classes of stock, and accommodate the 83(b) election, QSBS treatment, and investor-friendly governance.

However, the entity decision should not be made solely on the basis of legal structure. It must also factor in the startup’s initial funding profile, intended growth model, and expected holding period. I’ve encountered founders who rushed into a C-Corp setup, only to discover that their bootstrapped, low-burn business would have benefited from a pass-through structure for the first 18–24 months. Others started with an LLC to preserve flexibility but missed QSBS eligibility because of a late C-Corp conversion.

The IRS does not look favorably on retroactive changes. Once an entity election is made and equity is issued, the tax implications are set. It is far better to model these paths upfront—through a simple three-scenario tax lens—than to spend thousands later unwinding avoidable complexity. A 30-minute conversation early on often saves years of financial clean-up.

Every Receipt Tells a Story—And Some Matter More Than Others

Early expenses are often messy. Founders use personal credit cards, reimbursements are inconsistent, and recordkeeping is light. This is understandable, but it is not sustainable. Tax filings rely on credible documentation. The IRS doesn’t accept intent. It requires proof.

I’ve seen startups lose valuable deductions because no receipts could substantiate meals, travel, or contractor payments. Worse, I’ve seen them trigger audits when expense classifications were exaggerated: R&D mislabeled as consulting, marketing claimed as capital expenses, or software subscriptions lumped into cost of goods sold. Founders should think of each receipt as a breadcrumb that connects an expense to a business purpose. Not every path needs to be perfect, but enough of them must be traceable.

More importantly, classification affects the company’s tax profile. The difference between expensing and capitalizing software, or between qualifying and non-qualifying R&D, often hinges on how expenses are categorized in the books. Startups should establish these policies early—not just for tax, but for accurate board reporting and investor trust.

The Cap Table Must Match the Tax Ledger

Equity is the lifeblood of most startups. However, few founders realize that equity decisions such as grants, options, vesting schedules, and 83(b) filings are not just legal exercises. They’re tax triggers. If they are not documented and reported correctly, they create mismatches that haunt a company’s filings for years.

I’ve encountered startups where 409A valuations were not refreshed for over a year, resulting in option grants issued below fair market value, violating Section 409A, and opening both the company and its recipients to IRS penalties. I have seen missing 83(b) elections for founders who assumed their lawyers handled it, but only to discover at exit that they were liable for ordinary income on appreciated stock.

Even more subtly, I have seen startups use spreadsheets as their cap table. While this seems harmless in year one, the risks are real. Spreadsheets are error-prone, lack audit trails, and often fail to accurately reflect vesting. As the company grows and investors conduct diligence, mismatches between the cap table and tax records raise doubt. And doubt in a fundraising process is expensive.

The solution is simple: invest early in a cap table management system and ensure that every grant, issuance, and conversion is tracked not just legally, but also from a tax posture.

Nexus Is Not Optional—Remote Employees Create Filing Obligations

The distributed nature of startups has led to one of the most overlooked tax exposures: state nexus. The presence of a remote employee, contractor, or even a customer in a different state can trigger income, franchise, and sales tax obligations. These are not discretionary. They are enforceable, and states have become aggressive in pursuing them, especially as they seek to replenish revenue post-pandemic.

Founders often discover these exposures late during funding rounds or acquisition diligence, when investors request proof of state tax compliance. One company I advised had remote employees in five states and was registered in only one. By year three, they had exposure to multiple years of back taxes, penalties, and interest, none of which were budgeted for or known until it jeopardized a $10 million Series B.

Nexus rules vary by state, but the principle is consistent: if you have economic or physical presence, you are likely to owe something. Tracking this presence and registering accordingly is not optional. It is foundational. Early consultation with a tax advisor can help identify exposure zones and mitigate liabilities before they become real costs.

A Tax Advisor Is Not Just for Filing Season

Startups often view tax advisors as seasonal vendors, engaged only once a year to prepare returns and ensure compliance. This view is shortsighted. A tax advisor, particularly one who understands the nuances of startup finance, can add strategic value across entity selection, compensation planning, R&D credit analysis, international expansion, and M&A preparation.

The most successful early-stage companies I’ve worked with treat their tax advisors as part of the strategic brain trust. They involve them during product planning to evaluate sales tax implications, during hiring sprees to validate payroll compliance, and during fundraising to model after-tax scenarios for founders and early employees. In doing so, they avoid blind spots and gain leverage.

Founders often resist this partnership, citing cost or perceived complexity. But waiting until year-end to engage tax advisors is like calling a doctor after symptoms turn chronic. Early intervention is cheaper, easier, and far more effective.

Filing Is the Output. Discipline Is the Input.

Ultimately, tax filings are not where mistakes begin; they are where errors appear. The filing is the artifact. The fundamental determinant of tax clarity lies in daily behaviors, including maintaining clean books, implementing thoughtful policies, and fostering cross-functional communication among finance, legal, and leadership. Founders who understand this elevate taxes from a reactive cost to a proactive advantage.

The best companies build muscle memory around tax awareness. They train department heads on expense classifications. They align product strategy with sales tax compliance. They design equity plans with exit scenarios in mind. They know that tax posture shapes not only cash flow but credibility. In today’s competitive capital markets, credibility is a valuable currency.

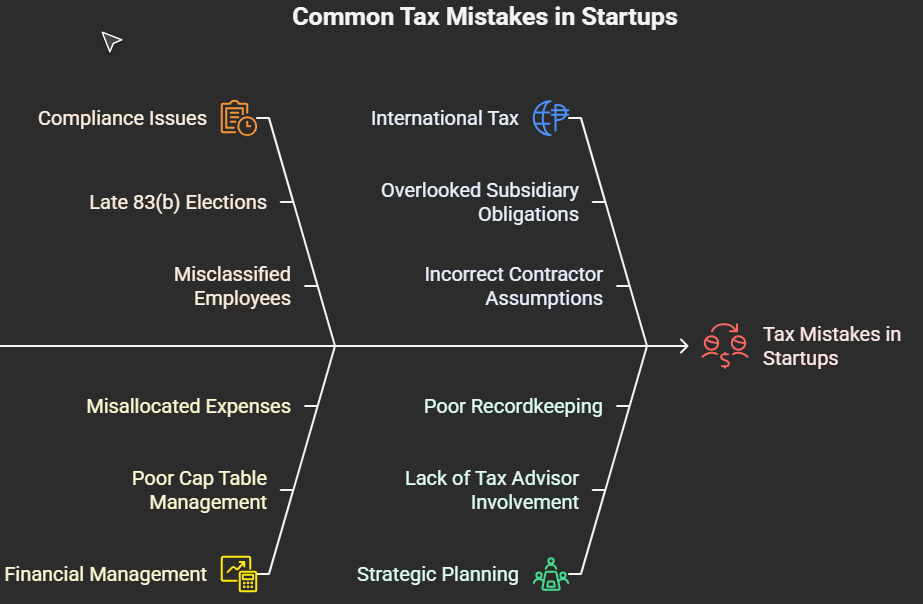

Top 20 Tax Mistakes for Startups (Series A–D, Including International Subsidiaries)

- Failing to file 83(b) elections on time.

- Neglecting 409A valuations and issuing mispriced options.

- Assuming QSBS eligibility without monitoring ongoing compliance.

- Using spreadsheets instead of proper cap table management systems.

- Misclassifying employees vs. contractors, leading to payroll tax penalties.

- Ignoring multi-state tax nexus from remote employees.

- Overlooking international subsidiary tax obligations (transfer pricing, VAT, withholding).

- Poor documentation of R&D credit claims.

- Misallocating expenses between capital vs. operating.

- Missing quarterly estimated tax payments.

- Treating stock options incorrectly under Section 409A.

- Overlooking state-level franchise and gross receipts taxes.

- Failing to track NOLs (net operating losses) as deferred tax assets.

- Not preparing for ASC 606 revenue recognition impacts.

- Underestimating sales tax obligations on SaaS or digital services.

- Missing equity documentation and board approvals.

- Assuming international contractors do not trigger tax obligations.

- Not involving tax advisors during fundraising or M&A negotiations.

- Poor recordkeeping leads to failed diligence.

- Treating tax advisors as seasonal vendors rather than strategic partners.

Disclaimer: This blog is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, tax, or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax advisor or counsel for advice tailored to your specific situation.

Hindol Datta, CPA, CMA, CIA, brings 25+ years of progressive financial leadership across cybersecurity, SaaS, digital marketing, and manufacturing. Currently VP of Finance at BeyondID, he holds advanced certifications in accounting, data analytics (Georgia Tech), and operations management, with experience implementing revenue operations across global teams and managing over $150M in M&A transactions.